The Labyrinth of Being (2023 – 2025)

Toward a Visual Ontology of Consciousness: Painting the Aporias of Subjective Experience

Exhibitions held at various institutions in multiple countries

The Labyrinth of Being (2023 – 2025)

Toward a Visual Ontology of Consciousness: Painting the Aporias of Subjective Experience

Exhibitions held at various institutions in multiple countries

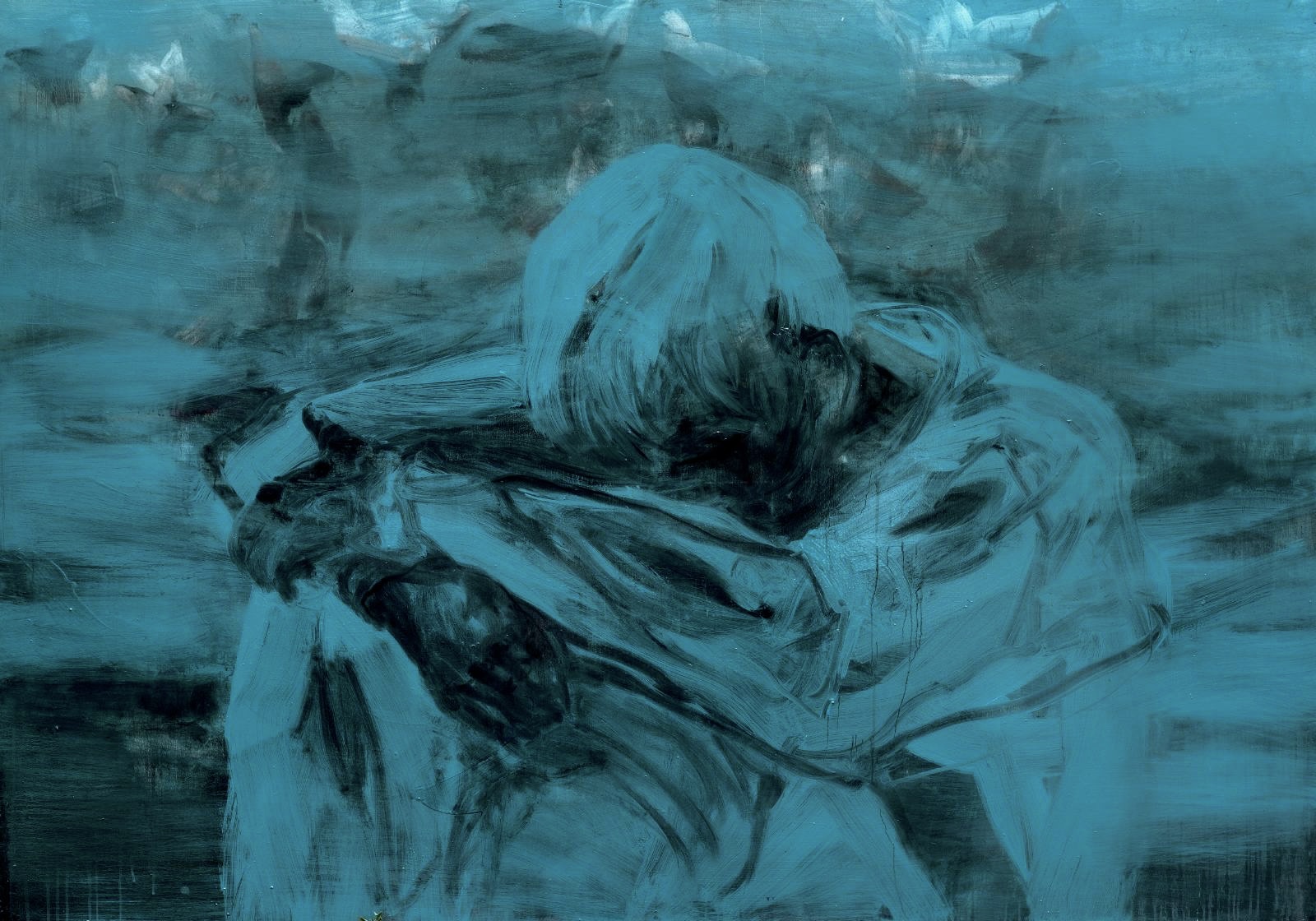

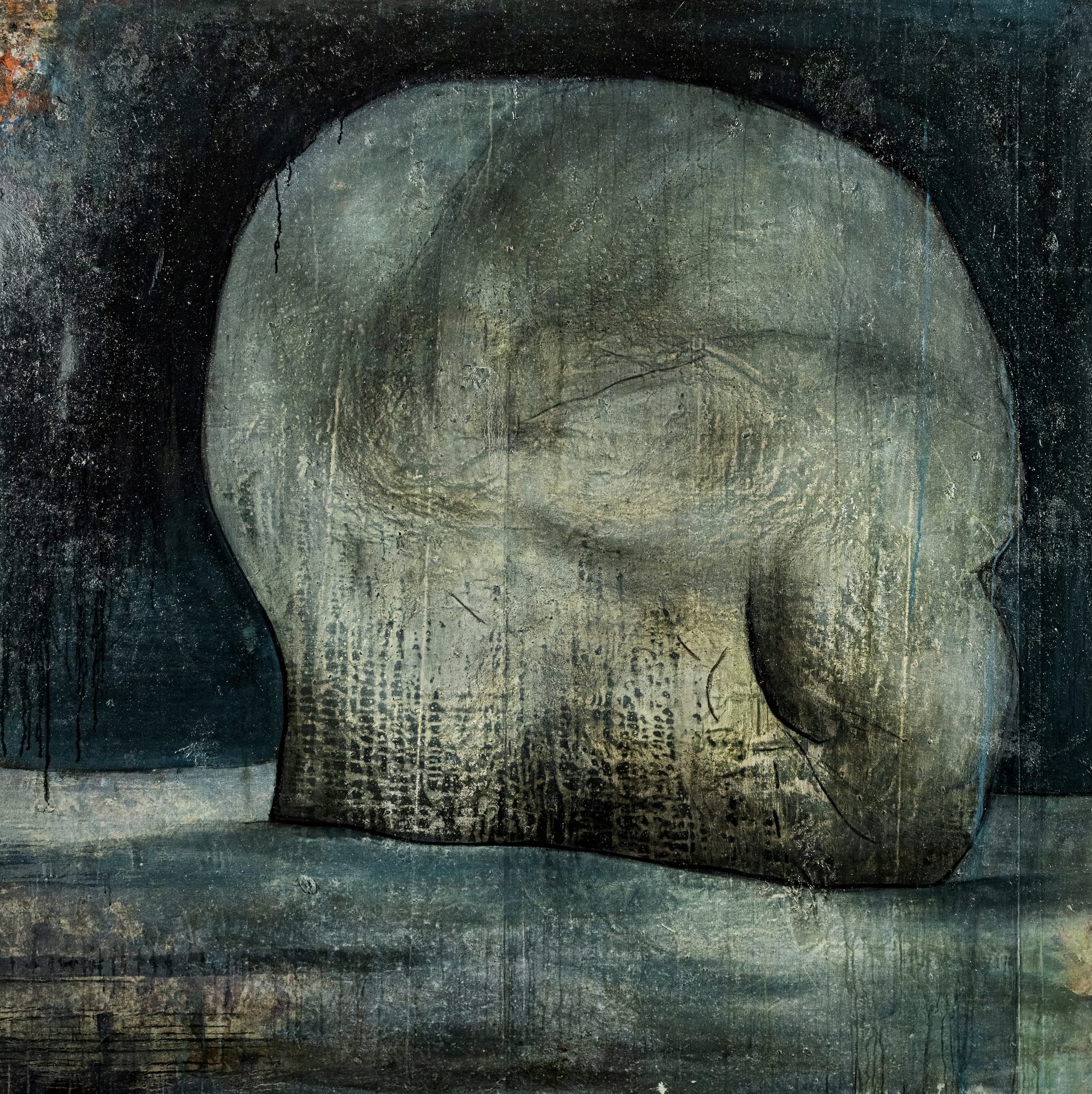

The Man in Black, oil on linen canvas, 160x160cm, 2024 (Private Collection)

The Man in Black, oil on linen canvas, 160x160cm, 2024 (Private Collection)

The Labyrinth of Being: A Philosophical Analysis of Gala’s Existential Aesthetics

Navigating the Paradoxes of Human Consciousness Through Contemporary Visual Ontology

Phenomenological Foundations: The Crisis of Meaning in Post-Modern Consciousness

Gala’s artistic corpus constitutes a profound meditation on what Heidegger termed Geworfenheit – the thrownness of human existence into a world not of our choosing. Her canvases function as phenomenological investigations into the structure of consciousness confronting its own contingency. Unlike narrative-driven artistic traditions that rely on temporal progression and character development, Gala’s work operates through what we might call “existential stasis” – a suspension of linear time that forces the viewer into direct confrontation with being-as-such. The absence of conventional plot structures in her work reflects a deeper philosophical commitment to presenting consciousness in its pre-reflective state, before the organizing principles of narrative impose artificial coherence upon the fundamental absurdity of existence. This approach aligns with Sartre’s conception of consciousness as néant – a nothingness that creates meaning through its very encounter with the resistant opacity of the world.

The Dialectics of Despair: Kierkegaardian Anxiety and the Aesthetic Dimension

The pervasive atmosphere of existential angst in Gala’s paintings cannot be understood merely as psychological portraiture but must be situated within the broader context of what Kierkegaard identified as the fundamental anxiety (Angst) that accompanies human freedom. Her mythical universe, populated by solitary figures struggling against incommunicable depths, embodies the Danish philosopher’s insight that despair is not merely a psychological condition but the very structure of human selfhood in its relation to the eternal. Gala’s characters exist in what we might term “ontological homelessness” – a condition that transcends mere social alienation to touch upon the more fundamental displacement of consciousness from any stable ground of being. This rootlessness reflects what Levinas called the “there is” (il y a) – the anonymous, impersonal being that precedes and exceeds individual existence, leaving the subject perpetually exposed to the weight of existence itself.

Aesthetic Autonomy and the Transfiguration of Suffering

The “art-for-art’s sake” aesthetic that governs Gala’s practice should not be understood as mere formalism but as a profound philosophical stance regarding the relationship between aesthetic experience and existential truth. Following the tradition established by Schopenhauer and developed by Nietzsche, Gala’s work suggests that artistic creation represents the only authentic response to the fundamental meaninglessness of existence – not through the provision of ready made meanings, but through the creation of forms that can bear the weight of meaninglessness without collapse.

Her commitment to aesthetic autonomy places her within what Adorno called the “negative dialectic” of modern art – the capacity of genuine artistic works to resist both the false consolations of traditional meaning-making and the nihilistic abandonment of all evaluative criteria. The quasi-divine status she accords to the artist reflects not hubris but recognition of art’s unique capacity to transform the raw material of suffering into forms capable of sustaining contemplative engagement.

The Ontology of Transformation: Death, Time, and Aesthetic Redemption

The presence of Thanatos in Gala’s work operates on multiple philosophical registers simultaneously. At the phenomenological level, the constant awareness of mortality that permeates her canvases reflects Heidegger’s insight that authentic existence (eigentlich) emerges only through what he called “being-toward-death” (Sein-zum-Tode) – the recognition that ourfinite temporal structure is not an accident but the very condition of meaningful choice and action. At the aesthetic level, the transformation of mortality into visual form represents what Benjamin called the “aura” of the work of art – its capacity to make present what is essentially absent, to give form to the formless. Gala’s paintings achieve what Bataille termed “sacred transgression” – the violation of normal boundaries that reveals the sacred dimension of existence through its very prohibition.

The Hermeneutics of Concealment: Truth as Un-concealment in Visual Form

The simultaneous revelation and concealment that characterizes Gala’s work reflects a sophisticated understanding of truth as aletheia – the Greek concept of truth as un-concealment that Heidegger recuperated in his later philosophy. Her paintings do not simply represent pre-existing truths but actively participate in the process by which truth emerges from concealment. The metaphor of keys without specified locks suggests that aesthetic experience operates through what Gadamer called “fusion of horizons” – the creative encounter between the world of the work and the world of the interpreter that generates meaning neither could produce alone. This hermeneutical structure transforms the viewer from passive consumer to active participant in the work’s ongoing self-interpretation.

The Ethics of Aesthetic Encounter: Responsibility and the Face of the Other

Despite its apparent solipsism, Gala’s work ultimately opens onto ethical questions through what Levinas called the “face-to-face” encounter with the Other. The extreme situations with which she identifies force both artist and viewer to confront the limits of their own capacity for empathy and understanding. This confrontation with extremity serves not to sensationalize suffering but to reveal the ethical demands that the reality of others’ pain places upon consciousness. The “burdens that a person today can take upon before breaking” that Gala explores in her work represent not merely psychological limits but the ethical boundaries of human responsibility. Her paintings ask not only “What can we bear?” but “What are we obligated to bear?” – questions that extend far beyond the aesthetic domain into the heart of ethical existence

Conclusion: Art as Ontological Resistance

Gala’s corpus represents a sustained attempt to preserve what Marcuse called art’s “negative” function – its capacity to refuse reconciliation with an unreconstructed reality while simultaneously avoiding the false consolations of pure escapism. Her paintings achieve what genuine philosophical art has always accomplished: they make visible the invisible structures of existence without reducing them to mere objects of theoretical knowledge. In an age of increasing technological mediation and commodified experience, Gala’s work stands as testimony to art’s continuing capacity to serve as what Heidegger called a “clearing” (Lichtung) – a space in which Being can show itself in its unconcealment. Her aesthetic practice thus constitutes not merely cultural production but active participation in the ongoing struggle to preserve spaces of authentic human dwelling within an increasingly administered world.

The tragic beauty that emerges from this struggle represents neither despair nor false consolation but what we might call “ontological courage” – the willingness to remain present to existence in its full complexity without either denial or premature synthesis. In this respect, Gala’s work continues the great tradition of philosophical art that recognizes aesthetic experience as an irreducible dimension of human truth-seeking, one that complements but cannot be reduced to either theoretical analysis or practical action. Through her unflinching engagement with the deepest questions of human existence, Gala demonstrates that authentic artistic practice remains one of our most powerful resources for what Rilke called “learning to see” – the patient cultivation of attention to the world as it actually presents itself, rather than as we might wish it to be or fear it must become.

The Labyrinth of Being: A Philosophical Analysis of Gala’s Existential Aesthetics

Navigating the Paradoxes of Human Consciousness Through Contemporary Visual Ontology

Phenomenological Foundations: The Crisis of Meaning in Post-Modern Consciousness

Gala’s artistic corpus constitutes a profound meditation on what Heidegger termed Geworfenheit – the thrownness of human existence into a world not of our choosing. Her canvases function as phenomenological investigations into the structure of consciousness confronting its own contingency. Unlike narrative-driven artistic traditions that rely on temporal progression and character development, Gala’s work operates through what we might call “existential stasis” – a suspension of linear time that forces the viewer into direct confrontation with being-as-such. The absence of conventional plot structures in her work reflects a deeper philosophical commitment to presenting consciousness in its pre-reflective state, before the organizing principles of narrative impose artificial coherence upon the fundamental absurdity of existence. This approach aligns with Sartre’s conception of consciousness as néant – a nothingness that creates meaning through its very encounter with the resistant opacity of the world.

The Dialectics of Despair: Kierkegaardian Anxiety and the Aesthetic Dimension

The pervasive atmosphere of existential angst in Gala’s paintings cannot be understood merely as psychological portraiture but must be situated within the broader context of what Kierkegaard identified as the fundamental anxiety (Angst) that accompanies human freedom. Her mythical universe, populated by solitary figures struggling against incommunicable depths, embodies the Danish philosopher’s insight that despair is not merely a psychological condition but the very structure of human selfhood in its relation to the eternal. Gala’s characters exist in what we might term “ontological homelessness” – a condition that transcends mere social alienation to touch upon the more fundamental displacement of consciousness from any stable ground of being. This rootlessness reflects what Levinas called the “there is” (il y a) – the anonymous, impersonal being that precedes and exceeds individual existence, leaving the subject perpetually exposed to the weight of existence itself.

Aesthetic Autonomy and the Transfiguration of Suffering

The “art-for-art’s sake” aesthetic that governs Gala’s practice should not be understood as mere formalism but as a profound philosophical stance regarding the relationship between aesthetic experience and existential truth. Following the tradition established by Schopenhauer and developed by Nietzsche, Gala’s work suggests that artistic creation represents the only authentic response to the fundamental meaninglessness of existence – not through the provision of ready made meanings, but through the creation of forms that can bear the weight of meaninglessness without collapse.

Her commitment to aesthetic autonomy places her within what Adorno called the “negative dialectic” of modern art – the capacity of genuine artistic works to resist both the false consolations of traditional meaning-making and the nihilistic abandonment of all evaluative criteria. The quasi-divine status she accords to the artist reflects not hubris but recognition of art’s unique capacity to transform the raw material of suffering into forms capable of sustaining contemplative engagement.

The Ontology of Transformation: Death, Time, and Aesthetic Redemption

The presence of Thanatos in Gala’s work operates on multiple philosophical registers simultaneously. At the phenomenological level, the constant awareness of mortality that permeates her canvases reflects Heidegger’s insight that authentic existence (eigentlich) emerges only through what he called “being-toward-death” (Sein-zum-Tode) – the recognition that ourfinite temporal structure is not an accident but the very condition of meaningful choice and action. At the aesthetic level, the transformation of mortality into visual form represents what Benjamin called the “aura” of the work of art – its capacity to make present what is essentially absent, to give form to the formless. Gala’s paintings achieve what Bataille termed “sacred transgression” – the violation of normal boundaries that reveals the sacred dimension of existence through its very prohibition.

The Hermeneutics of Concealment: Truth as Un-concealment in Visual Form

The simultaneous revelation and concealment that characterizes Gala’s work reflects a sophisticated understanding of truth as aletheia – the Greek concept of truth as un-concealment that Heidegger recuperated in his later philosophy. Her paintings do not simply represent pre-existing truths but actively participate in the process by which truth emerges from concealment. The metaphor of keys without specified locks suggests that aesthetic experience operates through what Gadamer called “fusion of horizons” – the creative encounter between the world of the work and the world of the interpreter that generates meaning neither could produce alone. This hermeneutical structure transforms the viewer from passive consumer to active participant in the work’s ongoing self-interpretation.

The Ethics of Aesthetic Encounter: Responsibility and the Face of the Other

Despite its apparent solipsism, Gala’s work ultimately opens onto ethical questions through what Levinas called the “face-to-face” encounter with the Other. The extreme situations with which she identifies force both artist and viewer to confront the limits of their own capacity for empathy and understanding. This confrontation with extremity serves not to sensationalize suffering but to reveal the ethical demands that the reality of others’ pain places upon consciousness. The “burdens that a person today can take upon before breaking” that Gala explores in her work represent not merely psychological limits but the ethical boundaries of human responsibility. Her paintings ask not only “What can we bear?” but “What are we obligated to bear?” – questions that extend far beyond the aesthetic domain into the heart of ethical existence.

Conclusion: Art as Ontological Resistance

Gala’s corpus represents a sustained attempt to preserve what Marcuse called art’s “negative” function – its capacity to refuse reconciliation with an unreconstructed reality while simultaneously avoiding the false consolations of pure escapism. Her paintings achieve what genuine philosophical art has always accomplished: they make visible the invisible structures of existence without reducing them to mere objects of theoretical knowledge. In an age of increasing technological mediation and commodified experience, Gala’s work stands as testimony to art’s continuing capacity to serve as what Heidegger called a “clearing” (Lichtung) – a space in which Being can show itself in its unconcealment. Her aesthetic practice thus constitutes not merely cultural production but active participation in the ongoing struggle to preserve spaces of authentic human dwelling within an increasingly administered world.

The tragic beauty that emerges from this struggle represents neither despair nor false consolation but what we might call “ontological courage” – the willingness to remain present to existence in its full complexity without either denial or premature synthesis. In this respect, Gala’s work continues the great tradition of philosophical art that recognizes aesthetic experience as an irreducible dimension of human truth-seeking, one that complements but cannot be reduced to either theoretical analysis or practical action. Through her unflinching engagement with the deepest questions of human existence, Gala demonstrates that authentic artistic practice remains one of our most powerful resources for what Rilke called “learning to see” – the patient cultivation of attention to the world as it actually presents itself, rather than as we might wish it to be or fear it must become.

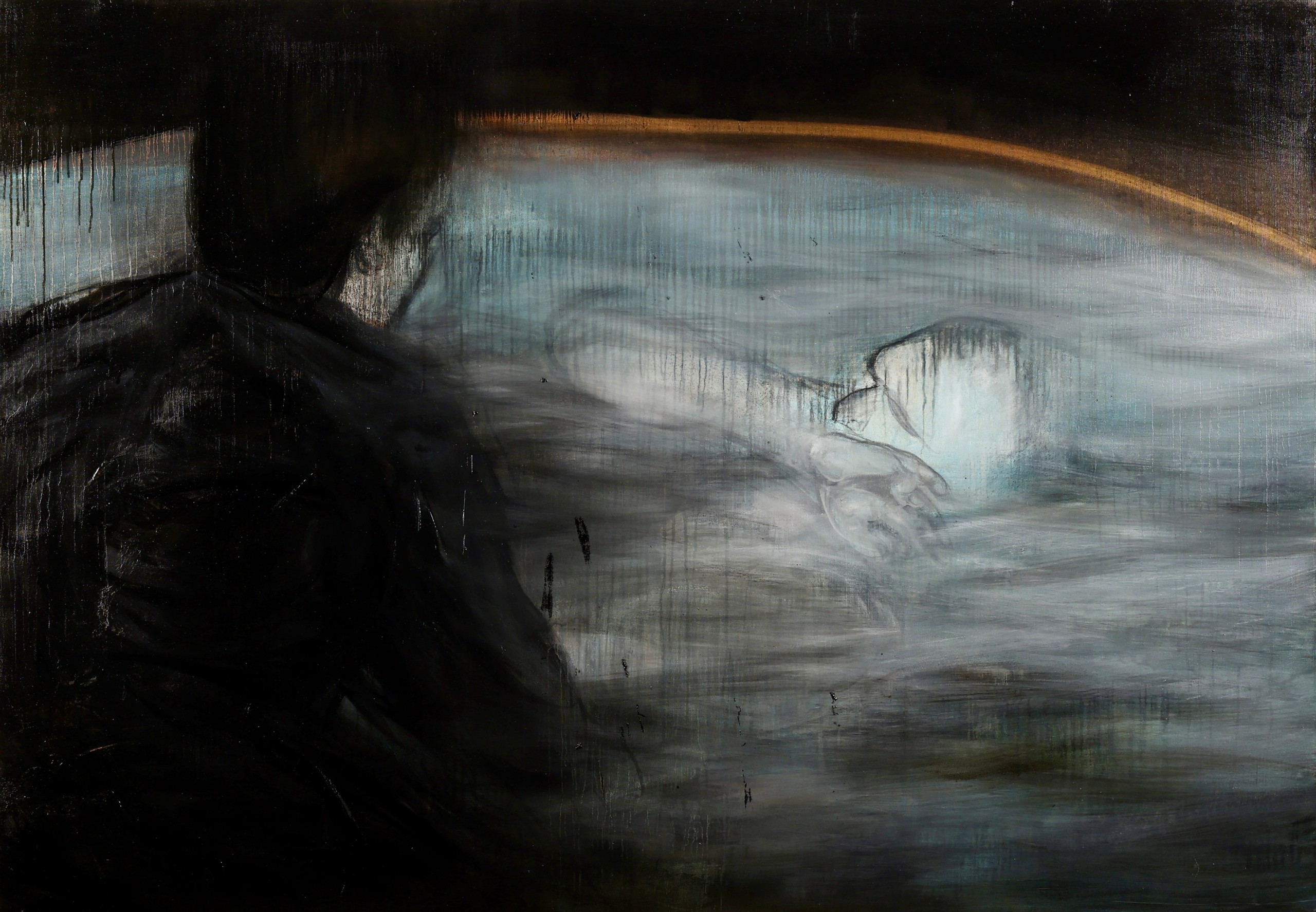

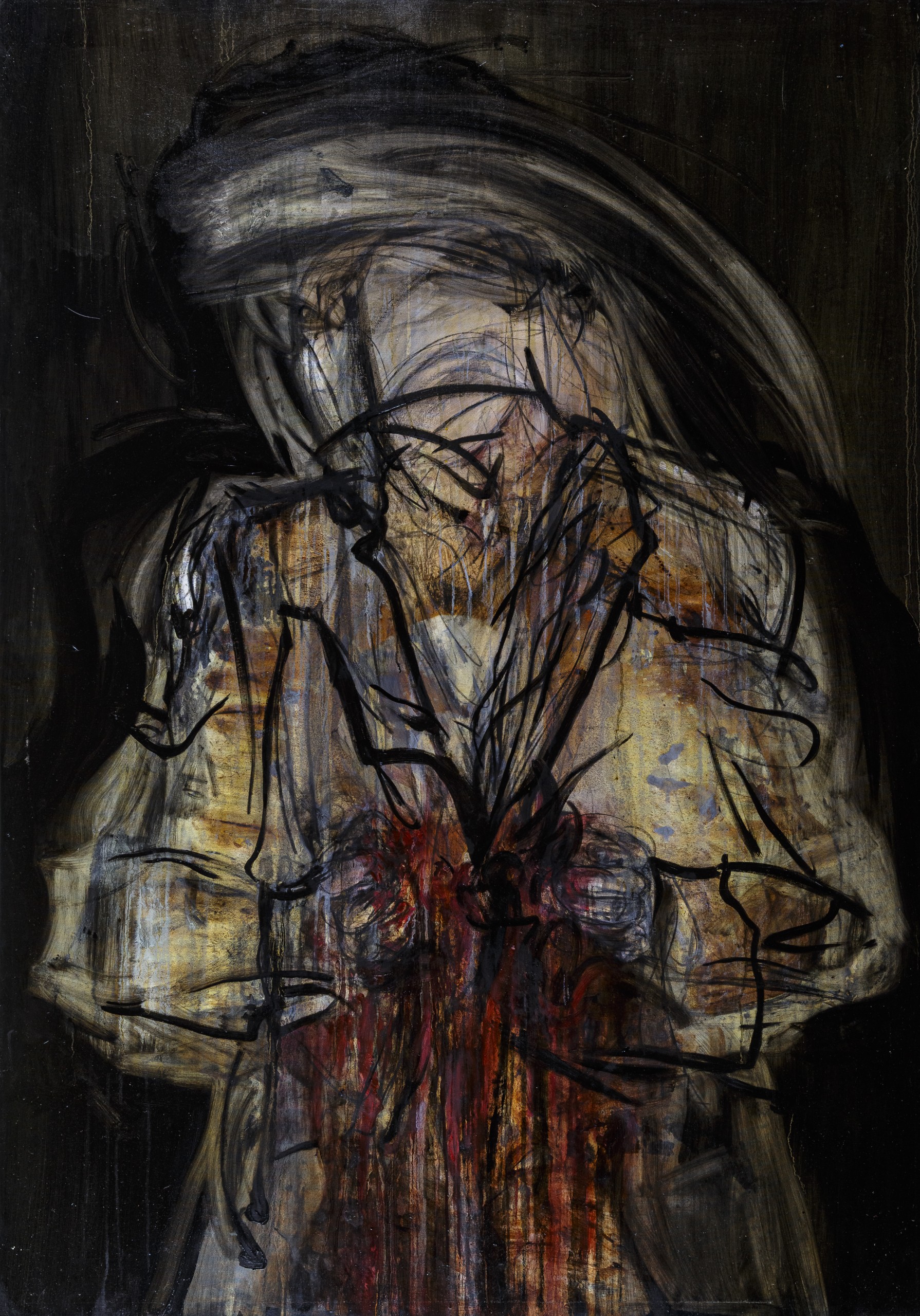

Free me, oil on canvas, 140x200cm, 2023

Free me, oil on canvas, 140x200cm, 2023

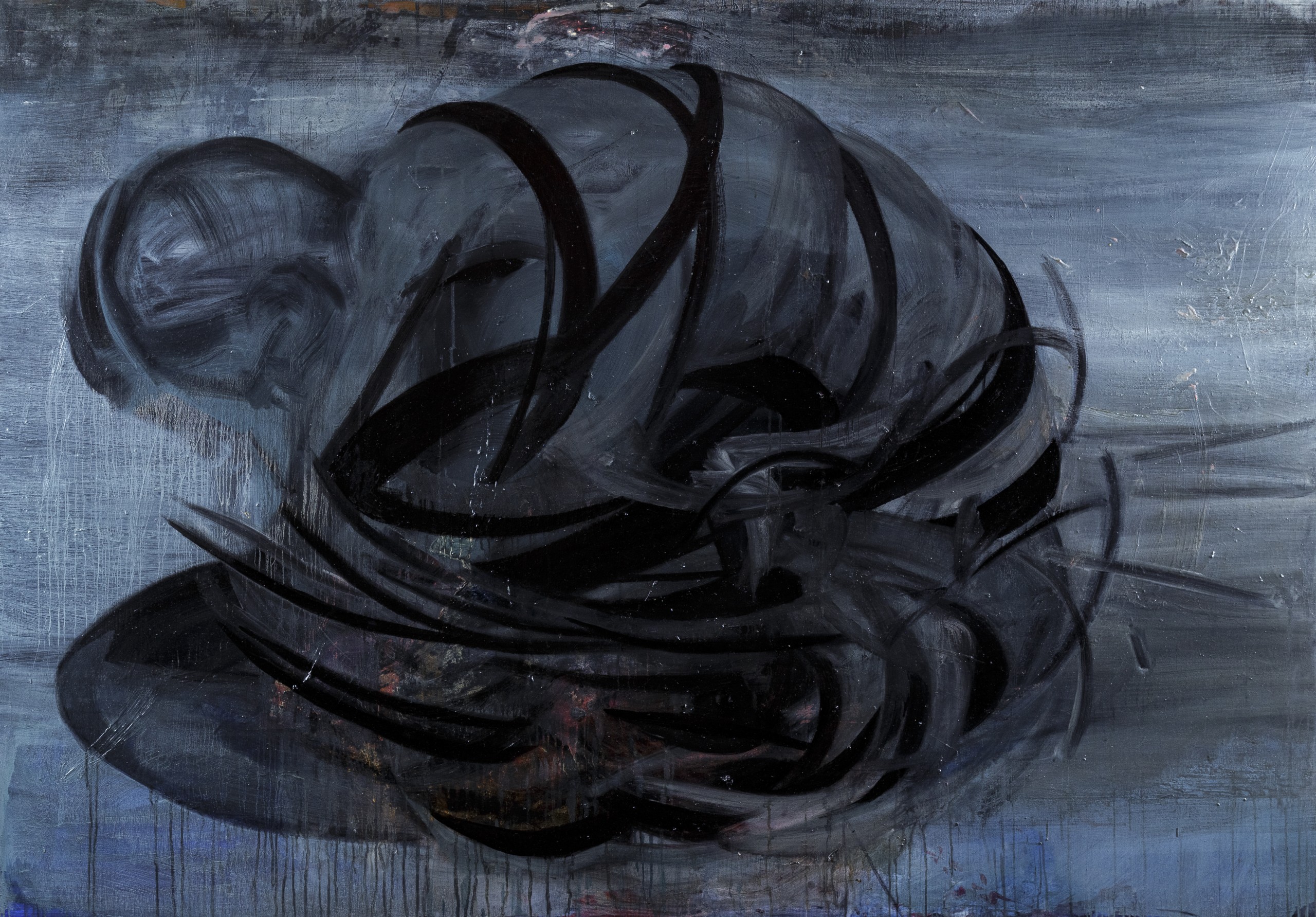

Beyond Vision, oil on canvas, 140x200cm, 2023 (Private collection)

Beyond Vision, oil on canvas, 140x200cm, 2023 (Private collection)